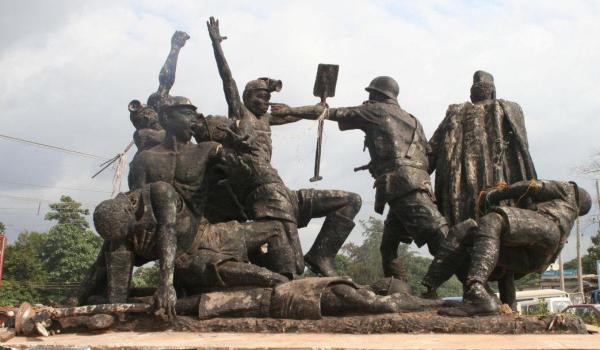

Even now, one can still hear the moans and cries of the 21 miners who were wrongfully slaughtered in the mines. The cries of the murdered souls that haunt Iva Valley have earned the Enugu coal mines the reputation of being haunted for more than 60 years.

21 miners, who were fathers, husbands, sons, and breadwinners, lost their lives in a hail of bullets nearly 70 years ago as they protested their difficult working conditions and were shot by the colonial police. This was one of the numerous reasons the Zikist struggle for independence (Nnamdi Azikwe) existed.

The legend’s narrative

The Udi coal mines were shut down, and the Iva Valley mines were constructed to take their place. The working conditions then deteriorated under the control of British managers, with instances of racism and physical abuse. In one instance, Mister T. Yates, a British national, slapped a worker named Mr. Okwudili Ojiyi on September 2, 1945. Mr. Ojiyi mustered the courage to report the assault, and Mr. T. Yates was charged with assault and punished.

Many of the terrible conditions persisted, though. The situation worsened on November 1, 1949, when the management refused the workers’ requests for the payment of rostering, the promotion of the mine hewers to artisans, and the payment of housing and travel expenses. As a result, the employees went on strike, which forced the British managers to fire more than 50 miners. This prompted the management to take action to remove all explosives from the mines on November 18 because they were concerned that the strike was related to the rising independence movements.

The explosives at Iva Valley proved challenging to remove after being removed from the Obwetti mines (a sister mine) very simply, in part because the employees refused to cooperate with management. The miners also concerned that if the explosives were taken out, nothing would stop the management from closing the mine (this was discovered by The Fitzgerald Commission, which the colonialists were forced to set up to investigate the massacre).

Captain F.S. Philip, a Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) from the United Kingdom, along with two other British officials and 75 armed local policemen were summoned to the mine to help remove the explosives just before anarchy was about to break out. The workers soon started singing, protesting, and making friends.

Phillip and his fellow Britons became uneasy as all of their racial stereotypes appeared to be playing out before their very eyes. They only saw threatening African workers and primitive natives. The Nation quotes Captain Phillip as saying that these individuals “were not industrial workers staging a protest, but ferocious, frantic natives, performing perilous dances and shouting nonsensical noises, preparing to attack.”

Hundreds of additional miners started to arrive, protesting and attaching red cloth to their wrists, knees, or helmets as a show of unity. The police party started to get impatient with the songs and numbers of solidarity at 1:30 pm. Investigations revealed that the Captain could only hear a “tremendous roaring and shrieking noise going on,” to which several guys danced “dangerously.” He gave the order for his troops to fire, then turned his revolver and shot Sunday Anyasado, a miner standing in front of him, in the mouth. The first victim was a young woman from Mbieri, Owerri who had just recently gotten married and had come to Enugu to work. She was instantly killed by a bullet fired by the Captain. Then, Livinus Okechukwuma, a machine operator from Ohi, Owerri, was shot by Phillip, also killing him. Okafor Ageni, an Udi tub man, emerged from the mine as mayhem erupted and said, “Anything wrong?” but was instantly shot and killed by a gunshot.

At the end of the chaos, 21 men had been shot dead and 51 men had been injured, including Sunday Anyasodo, a hewer from Obazu Mbezi, Livinus Okechukwuma, an engine driver from Amuzi Bende, Okafor Ageni, a tub man from Udi, Moses, an Umuohoho machine operator, Simeon, a Mbutu machine operator, Nnaji, the hewer from Ndibara Amaimo; Nwahu, the engine driver from Amuzi Bende and 15 others.

The Iva Valley miners’ Camps One and Two men who have been dubbed martyrs have only been relegated to urban legends, and November 18 has never been observed as a national day of mourning in Nigerian history. Even though the bodies and bullets are long gone, the dead miners’ eerie moans may still be heard in the depths.

If you don’t think the lore is true, visit the lovely coal city state and make your own judgments.